Men Have Suffered Too

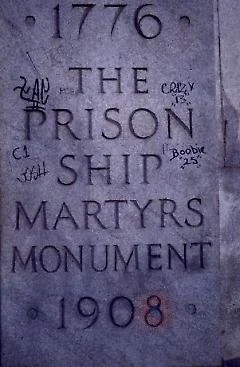

One of the greatest American monuments to human suffering is in Green Park, Brooklyn: The Prison Ship Martrys Monument. It memorializes 11,500 American POWs who died under horrific conditions on British ships---floating prisons---anchored off Long Island during the American Revolution.

One of the greatest American monuments to human suffering is in Green Park, Brooklyn: The Prison Ship Martrys Monument. It memorializes 11,500 American POWs who died under horrific conditions on British ships---floating prisons---anchored off Long Island during the American Revolution.

Every night, guards threw the garbage overboard: the bodies of young American men.

Every nation and people have their suffering stories. They are critical shapers of common identity: nothing is more unifying than we suffer together. But in our country have the suffering stories of some identities been elevated over those of others? And what does that mean for those whose stories have been sidelined?

For twenty-six years I counseled young men at an Ohio community college. Both my Black students and white, for different reasons, had limited awareness of their respective suffering stories. The former because their stories generally lacked firsthand chronicling; but also because such stories were always a problematic fit with the nation’s proud image of itself. But for those students, the needle is moving in the right direction. Despite textbook controversies, the acceleration of history projects nationally to draw back the veil on the suffering stories of Black Americans is robust and multi-faceted.

The young white men I counseled, by contrast, assumed they did not have a justifiable claim to historical suffering. No surprise after enduring years of K through 12 school history lessons which thematically implicate white males as oppressors. For how can oppressors suffer? Or, if they did, it was somehow optional. If white men died of hunger and cold at Valley Forge, it was because they were free to do so.

When I mentioned this marginalizing bias to my faculty colleagues their response was predictable: written history was always only about men---history---so move over! But as Eugene August, a pioneer scholar in Men’s Studies, wrote: “History is about a few men written by a few men for a few men.” We know about the lords of the manor because their portraits still hang in the manor house. But there are no portraits of the tenant farmers who toiled and died on their estate.

That said, a re-balancing to include the experiences of all Americans was always overdue. This was perhaps first set in motion---in spectacular fashion---with the 1974 publication of Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee. Topping the non-fiction bestseller list, in a single stroke it transformed popular perceptions of native Americans as movie bad guys into human beings who suffered. Moreover, for the first time the U.S. Calvary were the bad guys. A radical reversal. But fair.

But must re-balancing be a zero-sum equation? And what is the result when the only stories young white males hear about historical white men are the “oppressor stories”? We don’t know what the effect is on their collective psyches. But we do know, thanks to Women’s Studies, that negative messaging aimed at one gender will be collectively internalized over time.

When working with young men, I attempted, through group and individual counseling, to re-introduce them to “their” suffering stories. One of my most popular sources was the published journal of Private Jos. Plumb Martin, a farm boy who served seven years in the continental army during the American Revolution. Both my Black and white students viewed it for what it is: a young man’s personal narrative of physical hardships. Martin writes: “….if I stepped into a house to warm me, when passing, wet to the skin and almost dead from cold, hunger, and fatigue, what scornful looks and hard words have I experienced.”

Part of my students’ reaction was surprise, a sort of “That actually happened?” But there was also a therapeutic outcome. Attempting to simulate Martin’s many sleepless nights on cold ground, one student tried to sleep in his backyard on a frosty October night, like Martin having only a single woolen layer. He shivered for one hour and went back inside. But he connected with someone else’s suffering from the past, enabling him to appreciate and honor that suffering. More importantly, it helped him realize his own daily struggles were maybe not as bad as he thought.

In the canon of American suffering there should be room for both “Bury my Heart” and Jos. Plumb Martin. When our suffering stories are regulated or politicized, it risks obscuring their true pathos. A human condition we all have in common.

The unprecedented alienation among too many of our young men: James Shelley

Published: Jun. 15, 2022, 5:33 a.m.

An executive order by President Joe Biden early in his presidency that set up a White House Gender Policy Council failed to address the alienation and needs of young men in America, writes James Shelley in a guest column today. Recent mass shootings by disaffected young men suggest it's time for a reset. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

KIRTLAND, Ohio -- The recent -- and ongoing -- outbreak of mass shootings has brought renewed attention to the usual suspects of causation: loose gun laws, mental illness, or pathological hate. These are vital considerations as we grasp for answers. But there is something else we can do: Pay more attention to our young men.

For an individual to target and massacre innocents requires an unprecedented alienation. I have seen male alienation firsthand in my role as an adviser to male students at a community college. On an individual basis, there can be many complex reasons for this. But “the alienated” have this in common: They “hurt,” they can’t find a way in, and are usually emotionally isolated.

When I first met Robert (not his real name), a 22-year-old from a middle-class family, he was suffering a loss. His career dream was to become a drone pilot, but a driving-under-the-influence conviction made him ineligible for the required license. I advised him as he struggled to find an alternative pathway. He took three college classes during the day and worked part-time at a convenience store. Putting most of his income into keeping his car running, Robert wasn’t economically successful enough to live on his own, which led to strife with his parents. He could not find a way out, or in.

I am often surprised how alone these young men are. I see this whenever one enters my office to inform me he is homeless, usually because of a “fight” at home. I can help by arranging a short-term stay in a homeless shelter until family tempers cool. Before I do this, I ask: “Do you know someone you can stay with for a few nights? Other family? Friends?” Almost always, the young man will look at me and then out the window, saying nothing.

The young men I see who are alienated are nowhere near the extreme end. Because they seek guidance, they still sense a connection to the world, are still hoping to find a way. I lost track of Robert -- he dropped out and didn’t return my calls. I never thought his unhappiness would lead to violence, and it hasn’t. But I was worried it would lead to something else: a “death of despair.”

Young males are ahead of everyone in this category. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, the suicide rate for 15- to 24-year-old males is four times higher than for females of that age. More than 70% of opioid deaths are male. Young men also “fail to launch” at higher rates. Among 18- to 29-year-olds, 55% of males were still living with their parents in July 2020, as opposed to 49% of females.

In seeking help, men are up against an invisible bias. When a young, troubled male student enters my office, unconsciously, I am thinking that if he is in a bad place, it must be because he is 100% responsible for putting himself there, i.e., that he is fully to blame for his problems. If I am not attentive to this bias, he may get less of my empathy, meaning he will likely get less of my support.

This lack of empathy manifests on a societal scale. Virtually every college and university has a women’s center, offering dedicated support for women. By contrast, there are fewer than a dozen such programs nationally for college men.

One of President Joe Biden’s first executive orders was to create a White House Gender Policy Council. Among its primary missions was “to support women’s human rights“ and to “empower girls.” Despite the word “gender,” the council’s goals do not encompass issues affecting men and boys, or how to address them. Government is not yet interested in the well-being of males on a policy level.

It is humanly impossible to empathize with the Buffalo or Uvalde shooters, both extremely disaffected young men. But until we can structurally pivot from seeing males as the gender that does not need support, other measures -- more restrictive gun control, more accurate threat assessment, increased security, etc. -- may be able to mitigate mass shootings, but will never get to the root.

James Shelley is director of the Men’s Resource Center at Lakeland Community College in Kirtland, and author of the Cleveland novel, “The Deep Translucent Pond.”

Who will dare to be anchors of our new moral sanity?

Published: Apr. 16, 2025, 5:34 a.m.

Illustration by Chris Morris, Advance Local

By James Shelley

In the late Zygmunt Bauman’s 2000 book, “Liquid Modernity,” the British sociologist showed how modernity has swept us into an unstoppable, destabilizing liquid state of change. According to Bauman, the idealistic original goal of modernity was to “melt the solids” -- the decaying stabilities of the past -- in order to recast the new improved solids needed to get us to a utopian future. But at some point, modernity veered from this noble destination, instead compulsively sucked into the “melting and smelting” process itself.

One wonders -- 25 years after Bauman’s book was published -- if another sharp swerve is accelerating liquid modernity into a kind of hyper-fluidity. We can see the signs most alarmingly in the increasingly destabilizing realms of AI development and our unsettled national political leadership.

Governance from the party-in-charge -- in recent months, fueled by the “disruption” battle cry from an administration intent on solid-melting -- is now, like AI itself, flirting with a new and dangerous brink. Facilitating the rising power of both the “hyper-fluidities” of A1 development and Trump’s melting-of-all-solids approach to governance is a glaring deficiency: Both lack the staying hand of moral sanity.

In a recent article in Britain’s Spectator magazine, U.S. playwright Matthew Gasda wrote about how -- while researching his new play, “Doomers,” which looks at what AI means for our future -- he studied the “rock stars” of the AI world, hoping to get inside their heads. Perhaps most concerning, he found that, while these lofty technologists have no trouble developing statistical models about the likelihood of humanity’s end -- in which AI could have a starring role -- none of them “seemed to possess humanistic or theological intuition on why they should, perhaps, back away.”

Moral sanity enables the ethical ability to back away. In a broader sense, it is about having the wisdom and courage at the right moment to do the right thing for the common good, even if it means trying to stop, or at least slow, a seemingly unstoppable flow. It can mean risking one’s career. Or worse.

Around 391 of the Christian Era, a monk named Telemachus attempted to stop gladiatorial fighting in a Roman amphitheater. For this, the crowd stoned him to death. But it influenced Emperor Honorius’ banning of gladiatorial fighting. For Telemachus’ profound act of moral sanity, he was made a saint.

Nowadays, moral sanity martyrdom usually means the loss of one’s job or career. But moral sanity need not be limited to profound acts.

The oft-repeated defense for Trump’s wrecking-ball rollout of his economic agenda is to be patient, give it a chance. For those who remember the first months of Reaganomics in the 1980s, this is not an unreasonable argument. With one important difference. Behind the uncertainty of Reaganomics, even its critics could sense a steady hand. And always, a steady voice. President Ronald Reagan’s deep well of moral sanity exuded assurance that he would not wantonly melt all solids standing in his way simply because he could.

There are no such assurances from the current administration, nor from today’s AI accelerationists. In terms of the latter, no one questions that AI will engender unimagined medical advances and life improvements. But with no staying hand, it will also be indiscriminately used to replace as many human jobs as possible. Simply because it can.

The absence of the staying hand of moral sanity -- especially among our political and technological leadership -- is taking us, all of us, to a new and anxious place. Bauman, who died in 2017, would have characterized such a condition as “fear without an anchor and desperately seeking one.” It begs the question: Who will dare to be our new anchors? The field is wide open.

James Shelley taught Humanities at Lakeland Community College and is author of the novel, “The Deep Translucent Pond.”